Over the last couple of decades, we’ve become far more literate about food.

Mobile apps like Yuka, which let people scan the barcodes of food and other personal-care products to instantly get a “health score,” have exploded in popularity. Millions of people around the world use Yuka to inspect what’s in their shopping carts and decide which items make it to the checkout.

Yuka’s popularity is largely due to an increased consumer awareness of the impact of food processing, particularly the impact of ultra-processed foods in people’s diets.

But people didn’t suddenly “discover” highly processed foods. The term began to make its way into the mainstream through a mix of science, culture, and anecdata.

First was the science. Awareness began through public health and nutrition research, with epidemiologists observing correlations between diets high in ultra-processed foods and diseases like obesity, type 2 diabetes, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. In the late 2000s, a nomenclature was developed to categorize foods by their degree of processing. This gave researchers language.

Scientific awareness was closely followed by people feeling the effects of this kind of food before they could explain them. People would talk about food comas, feeling hungry all the time, generally feeling “off,” or having unexplained weight gain.

Once discomfort was widespread, people began asking why, and ingredient literacy became mainstream. We began reading food labels, and we could actually understand what we were reading. People would say things like “If you can’t pronounce it…”

Media and culture gave it a narrative, and there were hundreds of books and documentaries that brought the science and the anecdotal evidence together and produced works such as Food, Inc, Fed Up, Cooked, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, In Defense of Food, What to Eat, and more.

Fast-forward to today, the developed world enjoys a more nuanced understanding of nutrition and food, and can make informed decisions about what we feed ourselves, leading to better health outcomes.

Something similar is now happening in our relationship with the digital world, particularly with how we consume social media.

Is it time to go offline?

Scientific studies have long linked, to varying degrees, screen time and social media usage to mental health outcomes. Studies have found a significant association between social media use and symptoms of depression, with more frequent use linked to lower subjective well-being. Research has also observed increases in depressive symptoms and suicide-related outcomes among U.S. adolescents after 2010, correlated with rising screen and social media use. A recent study observed that just 1 week of no social media usage improved mental health outcomes in young adults.

Hundreds of studies explore this relationship, each with its own nuances and limitations. And while correlation is not causation, the point is that there is growing scientific evidence that not all screen time is equal, and not all digital environments place the same demands on our minds.

The pull toward analog

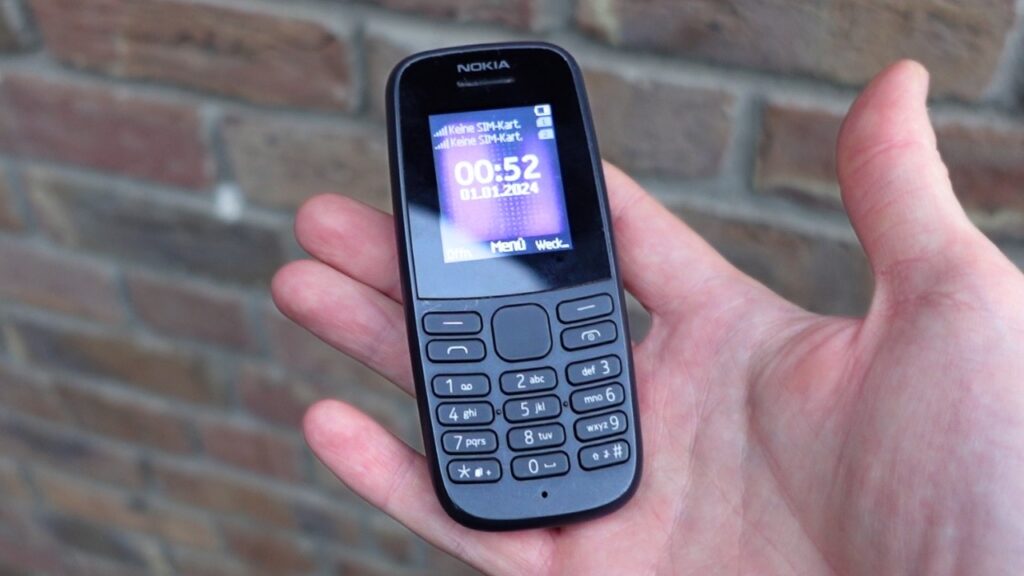

On the consumer front, internet discourse has recently centered on “touching grass,” as an appropriate intervention for those who are “chronically online.” To be told you need to touch grass is to be told that your relationship with social media has become unhealthy. As part of the “dumb-phone movement,” a growing number of people have begun switching from smartphones to so-called dumb phones, devices that let users call and text but don’t allow for “doomscrolling.”

The idea of a “dopamine detox” also gained popularity as a response to digital overstimulation. People pointed to digital devices, and activities like social media, gaming, and constant notifications, as the culprits of their feelings of burnout and brainfog. While neuroscientists have clearly debunked the science behind a dopamine “detox” (basically dopamine does not work like that), the term stuck, likely because it pointed to something that feels “real.”

This was followed by increased interest in film cameras, point-and-shoot digitals, notebooks, flip clocks, and even physical media (partly in response to the streaming industry). Marketers and media professionals are quick to point out that Gen Z is drawn towards nostalgia. But most of Gen Z are too young to be nostalgic for most of it. Under this context, this behavior likely has more to do with the fact that analog technologies introduce limits via friction. They slow things down in a world that feels too fast.

Diagnosis: brain rot

If touching grass and doing a “dopamine detox” are coping strategies, then “brain rot” would be the diagnosis. The term has become a catch-all to describe the “cognitive aftertaste” of spending too much time online, in the feeds. People point to difficulty concentrating, flattened curiosity, shortened attention spans, and memory issues. While the term is often used humorously, humor here is really a mask, and behind it is a growing sense that these environments are taking a real toll on how we think and feel.

Notably, brain rot is not blamed on the internet as a whole. It’s blamed on a specific kind of content environment, a specific ‘content diet’ (wink wink), one that is dominated by repetition, low-effort novelty, recycled formats, influencer frenzy, and constant stimulation. A content environment dominated by highly processed content.

Highly processed content can be defined as any material that has been exclusively engineered for distribution and engagement, without regard to meaning. It’s designed to perform well in the context of sorting algorithms, often at the expense of depth, context, or originality. Typically, it will be easy to consume, easy to replicate, and crucially, easy to forget. Its goal is to keep attention moving, not to leave anything lasting behind.

While this definition may sound harsh, I’m not actually opposed to highly processed content. An occasional snack is not the issue. A diet built on snacks is.

AI slop: the final straw

And while we’re already looking at a problematic environment, I would be remiss not to mention AI slop, which I consider the final straw. If highly processed content was already straining the system, AI slop pushed it over the edge.

As people experiment with AI for content creation, algorithms are increasingly surfacing AI-generated content, and since AI lowers the cost of content creation to nearly zero, volume explodes, and quality goes down. When production becomes frictionless, quantity tends to overwhelm quality (care, context, originality, intent, judgment)

In Filterworld, Kyle Chayka observes that algorithms, which are optimized for engagement and scale, tend to flatten culture by rewarding sameness over distinction. What rises to the top of our feeds is not what’s most original, but what’s most familiar: trendy formats, predictable aesthetics, and repeatable ideas. And while AI slop didn’t create this condition, it definitely accelerated it. Content generation is getting cheap and fast. There’s a general sense, almost like a quiet murmur, that there is a lot of content out there, but little worth lingering on. AI slop took an already flattened landscape and pressed it thinner still.

The result is highly processed feeds. While this term is, to my knowledge, not yet an established one, it is inspired by well-studied concepts such as algorithmic curation, filter bubbles, and other work on how feeds influence behavior and attention.

The latest social trend is to opt out

All of this helps explain why people are now openly saying we should go offline.

The idea of logging off, deleting apps, and abandoning your social presence once sounded extreme. Today, it’s increasingly sounding like common sense.

I don’t think technology itself suddenly became problematic. The same way food itself didn’t suddenly become problematic. Having a diet high in ultra-processed foods may lead to negative outcomes, but that doesn’t mean you’ll quit food. It means you will be more discerning and intentional with what you eat.

Our dominant mode of digital consumption today feels over-processed, overstimulating, and even extractive, mainly because most of this time is spent on algorithm-driven social media feeds that tend to reward highly processed content. But going offline might not be the most optimal intervention. After all, social media continues to help people stay in touch, maintain friendships, and find a sense of belonging in ways that weren’t previously possible.

Perhaps deep down, people know this but lack a more precise way of describing what they want, which I’d argue is going off-algorithm. People are gravitating towards spaces the algorithm can’t reach: Discord servers, WhatsApp groups, Close Friends, and of course, real life. To places like Reddit where community is central and there is a subreddit for literally everything you can imagine. We are reaching out to friends for recommendations on what to watch. When not long ago, we relied on recommendation algorithms without thinking twice.

If what we’re looking for is indeed fewer algorithms mediating our every interaction, reducing our exposure to highly processed content, and being more intentional with what we consume and create, then the call to log off isn’t really a rejection of the digital/social world. It’s a rejection of the highly processed version of it.

Developing a healthier relationship with social media will be a highly individual process. While some people will step away entirely, I think most people will simply find ways to rebalance what and how they consume. In time, most people will come to recognize the extent to which sorting algorithms shape how we think and feel, and will choose to engage with them deliberately rather than by default. In parallel, I’m sure social platforms will respond in various ways. Just two weeks ago, Instagram launched “a new way to see and control your algorithm”

Instagram has always been a place to dive deep into your interests and connect with friends. As your interests evolve over time, we want to give you more meaningful ways to control what you see on Instagram, starting with Reels. Using AI, you can now more easily view and personalize the topics that shape your Reels, making recommendations feel even more tailored to you.

(Interestingly and FWIW, the post above is Adam’s most liked post in a while – he’s the Head of Instagram)

Instagram also launched Rings this year, an award for creators that recognizes “risk-taking, innovation, authenticity, and cultural influence, not just popularity or follower numbers.”

We’re excited to share something new: Rings – an award from Instagram that’s all about celebrating those who aren’t afraid to take creative chances and do it their way. Those who bring people together over their creativity, and deserve recognition.

It does take a special kind of courage to produce content that’s not specifically designed to thrive within an algorithm. When platforms start giving users more control and rewarding creativity over scale, it’s a sign that the old engagement-maximization model is losing its hold.

What this means for brands and creators

There is no single right level of presence, no universally optimal posting cadence, no specific format or content formula that guarantees brand relevance without some tradeoffs. Whether a brand belongs in a highly processed feed or risks becoming part of one is a strategic question, and it requires nuance. Rather than prescribing a fixed set of recommendations, brands should seek guidance from strategists who can articulate a clear role for the brand, who track how meaning and taste evolve, and who understand attention and motivation, along with creative leaders who value craft and human judgment.

Fighting for attention in the feed is passé

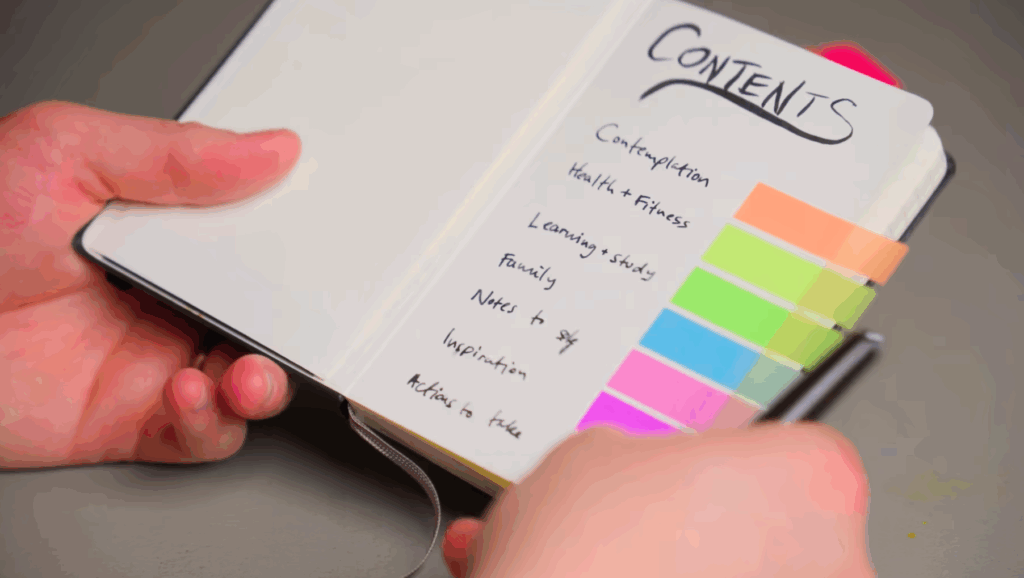

In a landscape increasingly shaped by highly processed feeds, certain areas appear more promising than others. Brands and creators will continue to find value in cultivating fandoms or communities. These are spaces where people return to because they feel invested, and not because content happens to surface. Others may benefit from being selective with where and how they show up – in contexts, environments, or ways where attention is more intentional. Some may invest more in optimizing content for recall rather than for casual engagements, the kind of work that leaves something behind (a feeling or a POV). Lastly, experimenting with formats that slow people down might prove valuable, think long-form essays, letters, series where ideas build over time, and craft-heavy work.

What comes next will demand taste, patience, and the confidence to put a premium on depth over visibility. In time, I believe this strategy will prove to be the most effective. Algorithms have historically evolved in response to abuse and/or saturation, such as when they began downranking clickbait or when Facebook introduced the meaningful social interactions (MSI) update to their news feed.

For years, much of the work in social marketing has focused on how brands should show up. Increasingly, the harder and more valuable skill may be knowing when not to show up at all, and having the discipline to act on it.

To the delight of many, myself included, far from dead, social might actually be on the cusp of a renaissance, one that rewards wholesome content, one that will make room for far more interesting work.

Food for thought.